A Fourth of July Story You Should Know

When Americans could be political enemies, and could rise above that for their country's sake

This is certainly the best and perhaps most famous Fourth of July story in American history. If you have been reading me for a long time, you may remember me telling this story before.

But even if you know it, it’s worth hearing again. John Adams, our nation’s second president, and Thomas Jefferson, the third, once friends and fellow revolutionaries, later became bitter enemies.

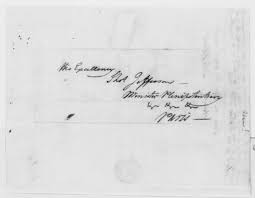

Letter, Adams to Jefferson

They each became leaders of America’s first two political parties, the Federalists and Republicans. When George Washington retired, Adams and Jefferson ran against each other, and Adams narrowly won. Four years later, Jefferson beat Adams.

John Adams was so bitter he packed up his belongings and left the new White House for his native Massachusetts before Jefferson’s inauguration — the only departing president ever to do so, until Donald Trump in 2021.

Thomas Jefferson served two terms, and then retired to Virginia forever.

The two old foes ignored each other. But as time went by, feelings and memories mellowed. Something else happened too: The other founding fathers they had made a revolution with began to die.

Washington was gone; so was Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Paine, and most of the rest. One day in 1812, out of the blue, Adams wrote Jefferson a letter wishing him a happy new year. Jefferson answered back.

They began corresponding. “You and I ought not to die before we have explained ourselves to each other,” Adams told Jefferson.

For the next 14 years, the men corresponded, writing about everything from farming to religion. Adams wrote more and was more comfortable expressing his emotions.

Adams at first wanted to argue politics, but Jefferson refused, saying “nothing new can be added by you or me to what has been said.”

They mostly avoided the subject after that, though there are indications that both felt they could have run things better than the generations of young whippersnappers who had come up after them.

Instead, they wrote about philosophy and books and their families. They never visited each other, or even seemed to have thought about doing so.

In that era of wooden-wheeled carts and dirt roads, when even railroads were still in the future, Massachusetts and Virginia were in some ways farther apart, especially for old men in declining health, than Washington and Australia are today.

Eventually, they began failing. John Adams was 90 in 1826, more than seven years older than Jefferson. He wanted to live till July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

The doctors didn’t think he could do it. He fell into a coma, only to awaken on that glorious day and ask, “Is it the Fourth?”

Told that it was, he brightened. He died late that afternoon, saying something like, “Thomas Jefferson survives.”

But in perhaps American history’s most amazing coincidences, Jefferson, age 83, had died several hours earlier.

Days later, when the news arrived, the nation was stunned. Many regarded this as a sign of approval for the United States of America from God himself. The not-yet-badly cracked Liberty Bell was rung to commemorate their memories.

Neither Jefferson nor Adams was by any means perfect. Adams could be irrationally emotional and as president approved the infamous Alien and Sedition Acts, a dangerous attack on free speech that sounds uncomfortably familiar today.

Thomas Jefferson, we now know thanks to DNA, took Sally Hemings, his teenage slave girl as his mistress and fathered numerous children with her — but never granted her freedom.

They had other faults too, and were about as different politically as two loyal Americans of their day could be.

Adams wanted a strong federal government; Jefferson, a weaker one, with strong state governments. Adams was completely opposed to slavery; Jefferson owned slaves.

Each had once beaten the other in presidential elections every bit as nasty and bitter as any contest today.

Yet in the end, they reconciled. They appeared to forgive each other, became friends again, and they both were loyal to the nation they had helped to create.

The men died exactly half a century after the Declaration of Independence was signed, a document Adams told Jefferson he should draft because he believed the Virginian was a better writer.

Nearly two centuries after they died on the same day, this nation still exists, and is once again deeply divided.

I cannot imagine Donald Trump ever trying to make up with Joe, though I can imagine Biden, a fundamentally decent man, being receptive to an apology, if Trump were capable of making one, which I fundamentally doubt.

But I would feel better about our nation if I could.

Nice 4th of July column. While both of these Founding Fathers died on that long ago holiday, their legacy continues on and still informs us. As Franklin said "A Republic, if we can keep it."

I love this inspirational story. Many of us are trying to do the same with our family members.